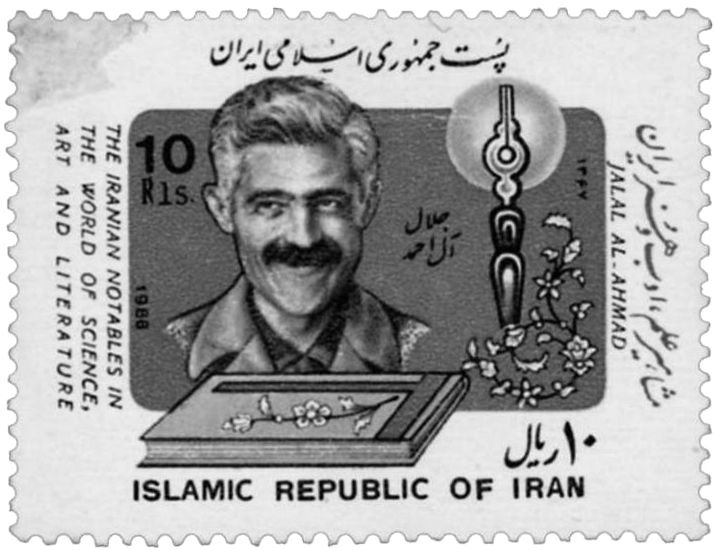

Review: Jalal Al-e Ahmad's 'Westoxification'

- Harriet Solomon

- Jul 23, 2022

- 14 min read

Introduction

Since its initial publication in 1962, Jalal Al-e Ahmad’s ‘Westoxification’ has been adopted, co-opted, and distorted by generations of Islamic revolutionaries and terrorist organisations alike. Considering his role in sparking not only revolution in Iran, but events further afield too, this essay seeks to determine the extent to which Westoxification can be linked to anti-western sentiment and its products since 1979.

Although the bloody consolidation of the Islamic Republic poses a challenge to historians seeking a ‘neutral’ reading of Al-e Ahmad,[1] when anachronistic moral judgement is avoided, manipulation of his original theory is illuminated. While his ideas have been weaponised by radical figures from Ayatollah Khomeini to Osama bin Laden, a closer reading of his ideology undermines suggestion that Al-e Ahmad was himself an Islamic fundamentalist. Instead, noting his modernist inclinations, resistance to nativism and tentative theological leanings, contemporary usage of Westoxification is best understood as an extremist interpretation of Al-e Ahmad’s initial ideas. The nuance lies however, in recognising that such co-option has been enabled by virtue of the nature of the theory itself. In his aversion to specificity and refusal to articulate a cure to the disease he diagnoses, the treatment for this sickness has been determined on his behalf. In discussion of Westoxification’s impact on Iran and on Islamic anti-westernism elsewhere, this essay seeks to distinguish between Al-e Ahmad’s original conceptions and the radical interpretations that have resulted from the malleability of his theory. While Westoxification succeeded in uniting Iranian people against a common enemy, situating their struggles within a broader context of colonial suffering, his tendency towards generalisation has provided an ideological tool kit been wielded by Islamic extremists for decades.

Historiography and Context

Three key areas of historiographical debate surround Al-e Ahmad’s Westoxification, all of which useful in informing a discussion on the manipulation of his original theory. Reminiscent of the ideas of Bernard Lewis, Liora Hendelman-Baavur identifies Al-e Ahmad as an anti-modernist.[2] In opposition to this reductive narrative that conflates anti-westernism with anti-modernism, this essay draws on the arguments of Farzin Vadhat and Shirin S. Deylami.[3] Using their illumination of Westoxification’s support for modernist progress outside of western conceptualisation, Hendelman-Baavur’s conclusions can be categorised among those interpretations based on the nature of Islamic Republic, as opposed to Al-e Ahmad’s theory as it was written. In a similar vein, and in reference to the work of Eskandar Sadeghi-Boroujerdi, this essay also rejects Abdollah Zahiri’s and Khalil Mahmoodi’s nativist readings of Westoxification. Although the regime that emerged in 1979 was indisputably nationalistic, suggesting Khomeini’s preoccupation with internal affairs to be a fair interpretation of Al-e Ahmad would be a failure to recognise both the wider context in which he wrote, and the global impact of his ideas.[4] Finally, and perhaps most importantly, historians remain in staunch disagreement as to the extent to which the revolution can be seen as a direct realisation of Al-e Ahmad’s text. While this essay is resistant to Hamid Algar’s suggestion that Westoxification ultimately led to revolution,[5] it equally seeks to demonstrate that it was in Ahmad’s unification of Iranian society against a common enemy that Khomeini and his peers were able to seize hold of the revolutionary discourse towards decidedly Islamic ends. As such, although Dabashi is correct in stressing that Al-e Ahmad himself was far from an Islamist fanatic,[6] it remains undeniable that his theory has provided a platform on which their ideas may be grounded.

To justify this essay’s historiographical position, a discussion on context is necessary. Son of a cleric and former attendee of the Najaf seminary in Iraq, Al-e Ahmad was well-versed in theology. Despite his background and the impact of his writing on the Islamic world, scholarship dedicated to contextualising his ideas within the history of Islamic ideology remains underwhelming. While individuals like Ibn Taymiyyah, Sayyid Qutb and Hasan al-Banna belonged to the Sunni branch of Islam, the resistance to anti-westernism and favour of Islamic revivalism documented in Shi’ite Al-e Ahmad’s writings is equally apparent in their works. Whether in Qutb’s theory of Jahiliyyah and its opposition to tyrannical rule,[7]al-Banna’s resistance to the spread of sinful ideology by British occupiers in Egypt,[8] or Taymiyyah’s condemnation of the Kufr (unbeliever),[9] a distaste for westernisation links Al-e Ahmad to generations of Islamic thinkers. While it is difficult to determine his personal familiarity with these ideologues, regardless of his exposure to their teachings, there is value in situating Westoxification within this longue durée of Islamic ideology. Although doing so in no way serves to legitimise claims of an inherent anti-westernism in Qur’anic theory, it does enable an understanding of how Al-e Ahmad can be elevated to a position similar to that occupied by radical Islamic thinkers that preceded him. In this, the scene is set for the eventual co-option of his ideas by extremist organisations that find legitimacy in the ideas of the individual.

To resign Al-e Ahmad solely to the realm of religion, however, would be a failure to appreciate the influence of wider intellectual theory. Having experienced the autocratic rule of Mohamad Reza Shah since his birth in 1923, he began to seek alternative outlets for his opposition to Iran’s decline under western-style leadership. Experimenting with communism during his membership to the Tudeh Party in the 1950s,[10] authoring politically engaged fiction, and reading widely on matters of Third Worldism in the works of Franz Fanon and Aimé Césaire, [11] Jalal Al-e Ahmad and his work are best understood as a product of a multifaceted and pluralistic environment.[12] Beyond a simple recollection of fact, this exercise in contextualisation succeeds in situating the theory of Westoxification within a broader history of theology and intellectualism. While Al-e Ahmad may have failed to anticipate the reach of his theoretical musings, their vast impact on both Iranian political discourse and the nature of radical Islam comes as no surprise considering the historical moment in which they were conceived. Although this context serves to demonstrate that a resistance to western infiltration was far from a revolutionary concept, it is exactly because of the popularity of these ideas that Al-e Ahmad’s summation of opposition to the west achieved such resonance.

Westoxification and the Islamic Republic

Over the course of its eleven chapters, Al-e Ahmad’s text diagnoses Iranian society and its inhabitants with a terminal illness; Westoxification. Although the term was coined by philosopher Ahmad Fardid in the 1950s, it was Al-e Ahmad that solidified its place in popular discourse. Highlighting a crisis of authenticity in Iran, his multi-dimensional volume undermines historic Persian ‘jealousy’ of the west,[13] instead illuminating the devastating role it has played in the degradation of Iranian civilisation. Whether owing to alienation by Qajar grandeur or Pahlavi mimicry of western superpowers, this battle with superficiality and the absence of an authentic Iranian identity had been at the forefront of the Iranian psyche for decades. When Al-e Ahmad wrote Westoxification (initially privately published and distributed clandestinely among friends and intellectuals),[14] he thus voiced the concern of generations with a fervour and focus previously unprecedented. Noting a system of top-down autocratic modernisation,[15] Al-e-Ahmad argued that consumer capitalism and its materialistic perspective had sparked the decay of humanity.[16] In framing his opposition in these economic, political, and arguably colonial terms, his arguments found resonance among everyone from secular intellectuals to religious clerics, uniting a society once segregated by differing ideological convictions.

While it is his diagnosis that sparked revolutionary unity in Iran, however, it is by virtue of his failure to provide a cure to the disease that this enthusiasm was harnessed for decidedly Islamic results. Despite merit to Gholam R. Vatandoust’s suggestion that Al-e Ahmad saw in ‘Shi’ism the vehicle to immunise society against the West’,[17] (particularly considering his recognition of clerical importance and employment of Qur’anic verse towards the end of his text), his theological convictions remain tentative. Refusing to advocate explicitly for the imposition of an Islamic state while simultaneously noting the desirable authenticity of faith, Al-e Ahmad sparked an open-ended discourse that enabled Ruhollah Khomeini and his associates to prescribe a religious regime as the cure to Iran’s western ailments. Drawing on Al-e Ahmad’s generalised discussion of colonial oppression, Khomeini utilised Westoxification’s Third Wordlist allusions and undefined receptivity to a theological solution to his advantage. Positioning Islam as a symbol of Iranian identity that offered the only defence in the battle between mostakbarin and mosta’zafin (oppressors and oppressed), while Westoxification may have ‘opened the road’ for a return to an authentic Iranian self, it was Khomeini that welcomed the responsibility of determining its nature.[18]

In addition to its discussion of symptoms, Westoxification also identifies the diseased. Criticising all Iranians, from intellectuals to everyday consumers, Al-e Ahmad draws on Fanon’s notion of colonised mentalities to demonstrate that individuals have succumbed to a life without ‘belief or conviction.’[19] Although he employs an economic framework, noting the western ‘machine’ as the embodiment of its infiltration (an approach likely linked to his early communist sympathies), Al-e Ahmad is careful to stress the extent to which the infection has spread. Having deemed much of society little more than imitations devoid of substance, the convictions of Ayatollah Khomeini (illuminated in his decisive campaign against the ‘Great Satan’), appeared as a direct and radical answer to Al-e Ahmad’s call for authenticity. To a community supposedly bereft of principle, this extreme approach was a seemingly desirable (at least when considering the desperation of Al-e Ahmad’s pleas) antithesis. As such, by virtue of its tentative Islamic musings and convincing identification of a problem requiring an immediate solution, Westoxification provided both a catalyst and justification for Khomeini’s Islamic Republic.

A Global Perspective: Westoxification and Islamic Terrorism

In 2001, the Taliban wielded the term ‘Westoxification’ as a label of condemnation against those who disagreed with their regime in Afghanistan.[20] In ISIS, owing to a belief in the necessity of violent severance of Westoxified associations, beheadings are utilised to initiate European-born recruits.[21] In Nigeria, Boko Haram have established an entire identity founded on a resistance to the Westoxification of society and its culture of corruption.[22] As such, although Khomeini’s religious repurposing of Westoxification in 1979 remains the most significant example of its radical interpretation, the link between Al-e Ahmad’s theory and Islamic extremism is extensive. In examination of three key organisations, this section of the essay thus seeks to demonstrate the weaponization of Westoxification by modern terrorist organisations, a process enabled by the malleability of Jalal Al-e Ahmad’s theory.

Owing to their links to Lebanese terrorist organisation Hizb’allah, in 1984 the United States designated the state of Iran as a terrorist sponsor. Sharing a conviction in the perils of Westoxification and equating the revolution of 1979 with a successful realisation of anti-western sentiment, Hizb’allah has consistently looked to Iran for both practical assistance and ideological inspiration.[23] Stating in their 1985 open letter a desire to ‘put an end to any colonialist entity’ in Lebanon, the organisation has claimed Khomeini as their ‘tutor and faqih’.[24] While there is little scholarship exploring Hizb’allah’s familiarity with Al-e Ahmad specifically, their advocation for the Islamic Republic’s ardent resistance to western infiltration (a sentiment grounded in the theory of Westoxification) demonstrates the elevation of his ideas to a position of reverence among Islamists seeking justification for their hostility towards western targets.

This is further evidenced in the relationship between Westoxification and Al-Qaeda. First and foremost, the terrorist organisation shares with Al-e Ahmad an opposition to the west. Articulated in a 2011 issue of their propagandic ‘Inspire’ magazine, the group applauds Iran’s success in conjuring a ‘rallying call’ for Muslims based on resistance to American aggression.[25] Although Westoxification is not noted by name, a contextual reading of Iranian history serves to demonstrate that this resistance was at least in part a product of Al-e Ahmad’s writing. Consider this alongside Osama bin Laden’s admiration for Iranian revolutionaries’ use of conflict with the west as a ‘Trojan horse’ for radical Islam, and the role of Westoxification in providing a foundation for extremist ideology is demonstrated.[26] Al-Qaeda’s conviction in the obligatory nature of jihad also derives inspiration from Al-e Ahmad. Reminiscent of his identification of westernisation in both internal (that is, Iran’s population) and external elements of society, bin Laden has expressed vocal support for both internal and external jihad.[27] In Al-e Ahmad’s resistance to both submission and nativism as responses to western infiltration (his book criticises those who simply ‘turn inwards’), links can be made to Al-Qaeda’s desire to spread the messages of Islamic extremism beyond national borders. Although their understanding of Westoxification has distorted Al-e Ahmad’s condemnation of western mimicry into a representation of westernisation as something inherently evil, it is by virtue of the text’s susceptibility to interpretation that such radical manipulations are made possible.

While both Al-Qaeda and Hizb’allah have utilised Al-e Ahmad’s theory as justification for their attacks on perceived external targets, Egyptian Al-Jihad was more focused on Westoxification’s legitimisation of radical action against tyrannical rule. Before his assassination in 1981, President Anwar Sadat embarked on a programme of westernised reform not dissimilar to that undertaken by the Shah in Iran. Identified as a prime example of Jahili rule by Al-Jihad’s ideological theorist Muhammad abd-al-Salam Faraj, Sadat might also be considered an embodiment of the diseased ‘occidentotic leader’ Al-e Ahmad condemns in his text.[28] As such, although the writings of Sayyid Qutb remain the primary source of inspiration for the Egyptian terrorist group, the links between their condemnation of apostate leaders and Al-e Ahmad’s opposition to the Pahlavi regime are clear. Consider this alongside Sadat’s well-evidenced opposition to Khomeini and support for the Shah, and Al-Jihad’s weaponization of Al-e Ahmad’s theory in pursuit of a similar change in leadership to that which took place in Iran is evidenced.[29]

These examples are not to suggest that Al-e Ahmad is alone the ideological inspiration for Islamic terrorism. In most instances, Westoxification’s theoretical resistance to western mimicry has been radically distorted by extremists for purposes far beyond what Al-e Ahmad might have anticipated. Despite these manipulations, however, in situating his theory within a wider history of radical Islamic ideology and considering the inspiration his anti-western sentiment has provided for organisations seeking justification for their hostility, the relationship between Westoxification and religious extremism is demonstrated.

Jalal Al-e Ahmad: Misunderstood?

Having exemplified how Westoxification impacted both the 1979 revolution, and the ideology of Islamic terrorist organisations since, this section of the essay seeks clarification. Although Al-e Ahmad’s theory certainly lent itself to radical interpretation, a closer reading of his text serves to illuminate the exact manner in which his ideas have been distorted. While scholars such as Liora Hendelman-Baavur have identified Al-e Ahmad as an anti-modernist (a label based on the nature of the Islamic Republic), much of Westoxification is in line with the tenets of modernism. In his reluctance to vilify the products of the west entirely,[30] his work is better read as a critique of the loss of subjectivity in Iran, rather than its shift towards modernism. While Khomeini and other Islamic fundamentalists tended to reject westernisation in its totality, Al-e Ahmad sought a world in which it might be utilised to Iranian advantage.[31] Similarly, and in contrast to the decidedly nationalistic sentiments of the Republic’s first Supreme Leader, a nativist reading of Westoxification is also misguided. Criticising those who ‘retreated into the shell of a national state’,[32] Al-e Ahmad opposed the kind of close-minded approach adopted by organisations like Hizb’allah. As such, although it is perhaps unsurprising that his ardent opposition to westernisation has been translated as advocation for ‘eastern’ nationalism, such an interpretation exists as another distortion of Al-e Ahmad’s original theory. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the extent to which Westoxification can be considered a theological document is debatable. While its ideology finds resonance in Islamic doctrine, Al-e Ahmad is adamant in his criticism of religious ‘superstition’ and outdated tradition.[33] While such discussion remains undeveloped, this critique raises questions regarding his confidence in clerical suitability for revolutionary leadership.[34] In this, more so than anything else, the ultimate contradiction of Westoxification is illuminated. Whether deemed a fatal flaw by those who stand in objection to the Islamic Republic and the extremism it has inspired or applauded as its greatest asset by Islamists around the world reconciled to a single cause, Westoxification’s failure to articulate a specific solution to the disease it diagnoses instils in its readers an unavoidable onus of interpretation.

Conclusion

Characterised aptly by Sadeghi-Boroujerdi as ‘insensitive, slapdash, imprecise and polemical’,[35] despite Al-e Ahmad’s intellectual background, this is not a text that boasts scholarly refinement. However, while the book is riddled with historical inaccuracies, half-hearted conclusions (‘please don’t ask me to go into details’),[36] and confusingly elaborate metaphors, it is precisely in the context of these ambiguities that the text’s impact on Iran and Islamic organisations further afield might be understood. In its convincing identification of a disease terminal to the authenticity of society, Al-e Ahmad captured the imagination of generations of revolutionaries resistant to western encroachment. Inspired by his condemnation of western materialism and its products, Westoxification has offered an ideological foundation for organisations seeking justification for their anti-western ideology since the 1960s. With decisive articulation of a cure to this disease notably lacking from Al-e Ahmad’s work, however, individuals from Khomeini to bin Laden have been able to situate the theory within a wider Islamic framework. Although closer examination of the text serves to demonstrate that these radical interpretations are something of a distortion of Al-e Ahmad’s original ideas (particularly considering his modernist inclinations and cautious religious sentiment), the impact of a theory so susceptible to distortion on the nature of Islamic anti-westernism is undeniable. As such, Westoxification is best considered as something of a lieux de memoire; a significant and symbolic site of memory visited, utilised, and ultimately radicalised by generations of Islamists around the world.

Harriet Solomon is currently pursuing an MA in Modern History at the London School of Economics.

Notes: [1] Eskandar Sadeghi-Boroujerdi, ‘Review: The Last Muslim Intellectual: The Life and Legacy of Jalal Al-E Ahmad, Hamid Dabashi’ (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2021), Iranian Studies (2022), p. 1. [2] Liora Hendelman-Baavur, ‘The odyssey of Jalal Al-Ahmad’s Gharbzadegi – Five decades after’ in Talattof, Kamran. Persian Language, Literature and Culture (London: Routledge, 2015), p. 261. [3] Shirin S. Deylami, ‘In the Face of the Machine: Westoxification, Cultural Globalisation, and the Making of an Alternative Global Modernity’, Polity, Vol. 43, No. 2 (2011), p. 244. [4] Eskandar Sadeghi-Boroujerdi, ‘Gharbzadegi, colonial capitalism and the state in Iran’, Postcolonial Studies, Vol. 24, No. 2 (2021), p. 174. [5] Hamid Algar, ‘Introduction’ in Ahmad, Jalal Al-I. Occidentosis: A Plague From the West (Berkley: Mizan Press, 1984), p. 8. [6] Hamid Dabashi, The Last Muslim Intellectual: The Life and Legacy of Jalal Al-e Ahmad (Edinburgh: Edinburgh Scholarship Online, 2021), p. 46. [7] Joshua J. Yates, ‘The Resurgence of Jihad and the Specter of Religious Populism’, The SAIS Review of International Affairs, Vol. 27, No. 2 (2007), p. 133. [8] Ran A. Levy, ‘The idea of jihad and its evolution: Hasan al-Banna and the society of Muslim Brothers’, Die Welt des Islam, Vol. 54, No. 2 (2014), p. 154. [9] Ibn Taymiyyah, The Religious and Moral Jihad (Birmingham: Maktabah Al Ansaar, 2001), p. 9. [10] Farzin Vadhat, ‘Return to which Self? Jalal Al-e Ahmad and the Discourse of Modernity’, Journal of Iranian Research and Analysis, Vol. 16, No. 2 (2000), p. 61. [11] Eskandar Sadeghi-Boroujerdi, ‘Gharbzadegi, colonial capitalism and the state in Iran’, Postcolonial Studies, Vol. 24, No. 2 (2021), p. 180. [12] Dabashi, The Last Muslim Intellectual, p. 281. [13] Jalal Al-e. Ahmad, Occidentosis: A Plague From the West, translated by R. Campbell (Berkley: Mizan Press, 1984), p. 43. [14] Hamid Dabashi, Theology of Discontent: The Ideological Foundation of the Islamic Revolution in Iran (New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 2006), p. 76. [15] Mehdi Faraji and Ali Mirsepassi, ‘De-Politicizing Westoxification: The Case of Bonyad Monthly,’ British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, Vol. 45, No. 3 (2018), p. 358. [16] Al-e Ahmad, Occidentosis, p. 133. [17] Gholam R. Vatandoust, ‘Review: Occidentosis: A Plague from the West, (Contemporary Islamic Thought Series’, Middle East Studies Association Bulletin, Vol. 19, No. 2 (1985), p. 237. [18] Vadhat, ‘Return to which Self?’, p. 67. [19] Al-e Ahmad, Occidentosis, p. 94. [20] Ahmad Rashid Salim, ‘The Taliban vs Global Islam: Politics, Power and the Public in Afghanistan’, Berkley Center (2021). [21] Robert J. Bunker and Dave Dilegge, Jihadi Terrorism, Insurgency and the Islamic State: A Small Wars Journal Anthology (Bloomington: XLIBRIS, 2017). [22] Suranjan Weeraratne, ‘Theorising the Expansion of the Boko Haram Insurgency in Nigeria’, Terrorism and Political Violence, Vol. 29, No. 4 (2017). [23] Daniel Byman, Deadly Connections: States that Sponsor Terrorism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012). [24] ‘The Hizballah Program: An Open Letter’ (1985), The Jerusalem Quarterly (1988) <https://www.ict.org.il/UserFiles/The%20Hizballah%20Program%20-%20An%20Open%20Letter.pdf> [Accessed 16 March 2022]. [25] Abu Suhail, ‘Iran and the Conspiracy Theories’, Inspire Magazine, Fall, Vol. 1432, No. 7 (2011). [26] Michael Doran, ‘The Pragmatic Fanaticism of al Qaeda: An Anatomy of Extremism in Middle Eastern Politics’, Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 117, No. 2 (2002), p. 184. [27] Yates, ‘The Resurgence of Jihad and the Specter of Religious Populism’, p. 134. [28] Al-e Ahmad, Occidentosis, p. 93. [29] Saad Eddin Ibrahim, ‘Anatomy of Egypt’s Militant Islamic Groups: Methodological Note and Preliminary Findings’, International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 12, No. 4 (1980), p. 438. [30] Deylami, ‘In the Face of the Machine’, p. 250. [31] Vadhat, ‘Return to which Self?’, p. 67. [32] Al-e Ahmad, Occidentosis, p. 74. [33] Ibid, p. 73. [34] Homa Omid, ‘Theocracy or democracy? The critics of ‘westoxification’ and the politics of fundamentalism in Iran’, Third World Quarterly, Vol. 13, No. 4 (1992), p. 677. [35] Sadeghi-Boroujerdi, ‘Gharbzadegi, colonial capitalism and the state in Iran’, p. 185. [36] Al-e Ahmad, Occidentosis, p. 79.

Comments